Lisa Stice:

Toward Antarctica by Elizabeth Bradfield

Made up of haibun-inspired poems and photography, Toward Antarctica chronicles Bradfield’s work in Antarctica. While the book follows in the footsteps of other polar explorers, this collection looks at this fragile region through the eyes of a naturalist to expose the environmental shifts. Toward Antarctica shares why it is so vital to protect this living ice that so many species call home and that so many other species the world-over depend upon to secure an environmental balance.

Raising by Vivian Wagner

Raising is a comprehensive look at motherhood. The poems move back and forth and sideways through time as Wagner reflects on her own mother and childhood, recounts memories of her own children, and enters into a new phase of empty-nester. It is the home we leave and the home to which we return. It is the past/present/future all at once, pushing forward through uncertainty with hopefulness.

Upside-Down Magic series by Sarah Mlynowski, Lauren Myracle, and Emily Jenkins.

These books have been a huge hit in the Stice household. The series follows Nory and her classmates as they struggle with self-esteem, identity, friends, bullying, and other difficult struggles of childhood with the addition of their magical powers not fitting the standards of the magical world in which they live. With a severe speech impairment (due to physical abnormalities) and short stature that puts her below the 1st percentile, my daughter has had a difficult time at school. She relates to the characters of the Upside-Down Magic class and has had the same bullying and self-confidence issues that they have had, and she’s found a strength in reading the books. Each character has something important to offer that no one with a standard power could provide. We’re on book #6 now. I’m also happy to share that my daughter has found her own real-life upside-down magic class because we’ve removed her from the traditional school that continued to be a place of exclusion and torment to her, and she is now in a tiny school that celebrates uniqueness.

Rebekah Sanderlin:

My New Year’s Resolution for 2019 was to read 52 books, roughly a book a week. This is nothing for some people, and I wouldn’t say it was a chore for me. I love to read and, as a writer, can easily justify the time spent with my nose in a book as being good for my professional development. That’s why I set that resolution, after all. I needed more beautiful words in my life and in my head.

So, I started, as I do with all resolutions, off great. I roared out of the gate with a shelf of to-reads and a fully loaded Kindle. And then, as my resolutions are wont to do, my commitment began to waver. Despite good intentions, I began falling behind schedule and had to get creative. I decided to allow myself the luxury of audiobooks. Audiobooks let me meet my reading goals while meeting many of my other responsibilities: driving, walking the dog, slogging through time at the gym (my perennial other resolution), and cooking dinner.

Without that accommodation, I wouldn’t have had the treat of Tom Hanks’ reading of Anne Patchett’s The Dutch House. Patchett is, of course, a master. A living legend. A woman I may or may not have slightly cyber-stalked because she lives in my hometown and I’m determined to find the one mutual connection we surely have who will someday agree to introduce me to her. But I digress…

The Dutch House, like her other fine books, weaves together the tiny details of the characters’ lives in a nuanced way that tells the dark and tragic, but utterly human, story of a brother and sister who are unable to overcome the greatest injustice of their young lives. For decades, their entire lives are dominated by their family home, or rather, their lack of a family home. (I won’t spoil it for you.)

I do not doubt that I would have loved the book just as much had I read the words for myself, but Tom Hanks’ smooth voice and perfect inflections heightened the experience so much that I found my daily step count increasing as I kept adding extra blocks to my walks with the dog and our nightly meals became much more elaborate as I looked for reasons to prolong the cooking.

But I didn’t only listen to books this year. I did a lot of actual reading, too. One of my favorites was Kristin Hannah’s The Great Alone, which I read early in the year, under blankets and in front of a fire, while snow still covered the ground outside where I live in Colorado.

The book is set in a remote part of Alaska, an ill-considered homesteading adventure that a not-so-stable family undertakes in the 1970s at the insistence of the father, an alcoholic grappling with his experiences fighting in Vietnam.

The family, father Ernt, mother Cora and 13-year-old daughter Leni, are as volatile as Alaska’s extreme seasons. As she always does, Hannah deftly crafts the characters as true people, not caricatures, which makes it odd that Ernt’s erratic and sometimes violent behavior is so conveniently pinned on his experiences in Vietnam, without more exploration of wider-ranging mental illness. That blame-it-all-on-PTSD kneejerk is something few in the military community will miss, and many will likely find as irritating as I did.

That aside, the novel is a gorgeous exploration of the wild Alaskan landscape, a young family’s dynamics, the sacrifices and accommodations people make for love, and the real impacts of war on soldiers and those who love them.

Which brings me to my third recommendation, Shatter the Nations: ISIS and the War for the Caliphate, by Mike Giglio. Anyone who has talked books with me lately has heard me gush about this one. Even months after reading, I’m still trying to process it. It may take me years, if ever.

Giglio is an American journalist who lived in and around ISIS territory for four years while reporting this stunning, non-fiction account of ISIS’ push into Iraq and Syria. Through his own journeys throughout the region, he tracks the terror group’s expansion and their impact on the people caught up in the middle and on both sides of the fight. The story is told narratively, almost as a memoir, and he presents all the people involved – the innocents, the smugglers, the American and Iraqi soldiers—as utterly relatable.

I found myself holding my breath as his own life is, repeatedly, in immediate danger, and I found myself weeping, for all the people – mothers, children, young and old men and women – living in this hellscape. Giglio masterfully writes about the absolute worst the world has to offer with such a necessarily light touch so as not to camp out on macabre and terrifying. With such a horrific subject matter, a less gifted writer would be absolutely unreadable.

Jennifer Orth-Veillon

In Richard Flannagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North, we follow doctor and Australian WWII hero Dorrigo Evans on a journey weaving past and present in a style I can only compare to the painterly technique of chiaroscuro – the bold blending of dark and light. And, as we see in the works of Caravaggio or La Tour, the sparse, well-crafted use of light is what gives volume and flesh to the darkness that could easily overrun the canvas.

The lighter parts of The Narrow Road to the Deep North are indeed both finite and vital. “Why at the beginning of things is there always light?” asks Dorrigo Evans in the book’s first sentence. The lightness in the storylines come in the form of Evans’ young adulthood under the unforgiving Australian sun as the young doctor awaits deployment in 1943. In an Adelaide book shop, he meets and falls in love with Amy, his uncle’s wife. He never sees her again after he leaves, but we learn that she was the only woman he ever loved.

Their affair, mostly played out on white beaches, runs in and out of the other, much darker storylines. Dorrigo is captured during WWII and is sent to a Japanese POW camp in Thailand where the prisoners are made to construct the Burmese railway. Save the occasional memories of Amy, no light shines here. Flannagan spares no details as we are plunged scene after scene into the horrifying universe of forced labor, starvation, disease, and death. We get the points of view from the sadistic Japanese camp commander, Nakamura, and from prisoners who steal each other’s rations. Evans, who administers medical aid and serves as mediator between the dying men and Nakamura, returns to Australia a celebrity but enters a dull mask of marriage with a rich woman who can’t keep his sexual interest.

However, his mind can’t stray from the war and we get glimpses of his obsession with not only the post-war lives of some of the repatriated prisoners, but also with the prisoners he was unable to save in the camp. We also get to follow Nakamura, who took on a false identity, escaped war tribunals and assured execution, and lived serene life with a woman he can’t believe loves him. This novel stays in its darkest place for so long, it’s easy to wonder if we’ve reached something like a painting’s vanishing point – the point where all the diagonal, vertical, and horizontal lines converge, giving us the perspective that we might never get out.

Light creeps back in though as we are made to accept Dorrigo Evans not for the heroic man he should be post-war, but for the man that he is – a man who decided to continue putting one foot in front of the other in the light despite living in a world populated by shadows. This echoes what he eventually says towards the book’s end, “The world is. It just is.”

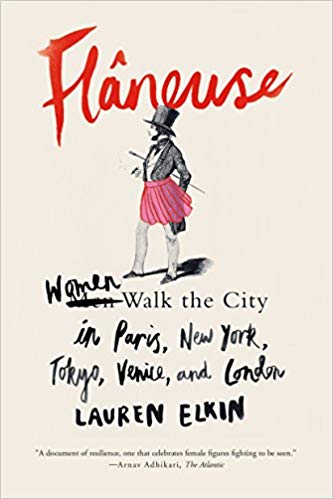

Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, London, and Tokyo by Lauren Elkin

The French verb “flâner” denotes the act of walking aimlessly and taking pleasure in contemplating spontaneous impressions experienced during passive observation of the surroundings. We most associate the noun, the person–the flâneur– with German cultural critic Walter Benjamin and French symbolist poet Charles Baudelaire, who roamed and loafed through Parisian streets and arcades leading them to develop some of the most influential artistic theories of all times.

But perhaps more importantly, we associate the flâneur with a male. Only a man, it seems, has the privilege and the freedom to wander the urban space alone, anonymous, unobserved.

But what about the woman, the “flâneuse?”

This is the concept Lauren Elkin takes on in Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, London, and Tokyo, a book that is, à la Susan Sontag, part memoir, part cultural criticism. Elkin celebrates the walking woman and presents her as a “determined, resourceful individual keenly attuned to the creative potential of the city, and the liberating possibilities of a good walk.” However, she also demonstrates that women’s claims to occupy urban space remains a subversive act.

In the cities of New York, Paris, Tokyo, London, and Venice, Lauren Elkin describes the famous flâneuses who inhabited their streets such as French filmmaker Agnès Varda, war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, or novelists George Sand and Virginia Woolf. Elkin reveals what happens each time an artistic woman goes out to meet the city, how each of her steps contributes to transforming not only her existence but also the existence of those live in the world around her. A very enjoyable read!

These images are not just photos. These images are meant to evoke a warrior sense. A feeling of what it must be like to have that special call to duty in the heart of every soldier https://mensbusinessbook.info

LikeLike