Like many other people, I was riveted this week by the odd spectacle of our current President shaking hands with former President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle at George H.W. Bush’s funeral ceremony. I was never a fan of the Bushes, and so not nostalgic on that account, but I was as interested in the footage as anyone else: watching Hillary’s straight-ahead stare (utterly earned), Jimmy Carter’s clear acknowledgement of Trump’s entrance followed by a crafty looking-at-his-watch trick, Dick Cheney’s dagger eyes as if he were hoping for another chance to shoot someone in the face.

What made the biggest impression on me, however, was Michelle Obama’s dignified handshake and then the look of thinly veiled disgust on her face as she sat back in her pinstriped pantsuit (a subtle support of Hillary?). How she must hate our current Prez; she must loathe the man. He’s done so much to stoke racial division, to undermine all that she and her husband worked for, to encourage the worst and ugliest impulses among an apparently susceptible American populace.

But this isn’t meant to be depressing. Watching Michelle force herself through this charade, I felt something a little more personal. Like many people, I have always felt a strong support of the Obamas, not only because I share their general politics and voted for Barack Obama both elections, but because my family has a small but meaningful connection to their family. Michelle Obama’s mother, Marian Robinson, who lived in the White House for eight years caring for Sasha and Malia Obama, is the former secretary of my great-uncle, Marven Tillin, from his time as a lawyer on the south side of Chicago.

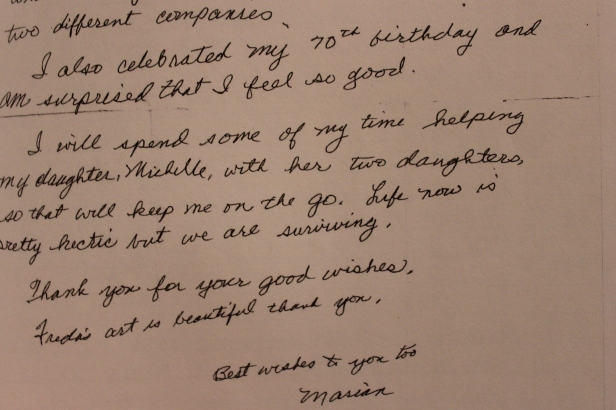

Theirs was an affectionate and lasting relationship. My great-aunt and uncle still have copies of letters Mrs. Robinson sent them every Christmas for many years. These letters have become family treasures. They are records of history but also, for me, serve as reassurances that my great-uncle was a kind and considerate person to work for, the sort who’d receive cards from former employees decades later out of mutual respect for one another.

Looking back through a book my great-Aunt Freda wrote after Marven’s passing, in which several of the letters from Marian Robinson are contained, I can see that they have been carefully preserved. I think I remember talk of an early letter wherein Mrs. Robinson mentions that Michelle is dating a “young basketball player from Harvard,” but I couldn’t find that letter in the collection, so perhaps I’m remembering wrong.

I did, however, find a letter mentioning Michelle’s upcoming engagement (above), and, most remarkably, the final letter, dated as late as Christmas 2007, in which Mrs. Robinson modestly notes that she will be devoting her time to helping Michelle care for the girls.

I can still remember Marven and Freda’s delight over Barack Obama’s election, and knowing that their old friend, Marian Robinson, was residing in the White House. They wrote to her there, but by that time, I think she was too busy to write back, or perhaps the note never reached her. But the affection and pride they felt in her family’s rare ascendancy was palpable. I think we all felt like we had the tiniest connection to something remarkable. Is there anything more delightful, more oddly funny and wondrous, than when personal life intersects with some great moment in history?

I remember my husband looking at the Obamas on the cover of TIME Magazine, after Barack’s first election. “What a beautiful family,” he said. “I love that they are the face of America to the world.”

—

My great-uncle Marven was born in what feels like another time: April 21st, 1931.

His Jewish grandparents had emigrated to the United States from eastern Europe. Always scholarly and serious, but with a cerebral and self-deprecating sense of humor, he endured the loss of his father at age five but grew into a kind, quiet, and self-assured young man, thanks in large part to the efforts of his mother.

He was the only Jewish member of our entire family, marrying Freda Torrisi, of staunchly Catholic, Sicilian descent, in 1962. He kept his Jewish traditions–I remember playing Dreidel with him on several occasions, as a child, with a dreidel he’d made himself out of clay–he made many things, like teapots and even a trough for curing homemade lox, out of clay–but also adopted many Sicilian cultural particularities with gusto. As Freda recalls, no one in her family could say Marven’s name well, and her Sicilian-born parents pronounced it more like “Marfina.”

But they accepted him readily, especially when they learned that he could cook. He was an eager student of their traditional recipes; he copied them out by hand and practiced many times until he had perfected them like a true Sicilian. His scacciata, or meat pie, was legendary.

Freda and Marven were married on their lunch break–she was a social worker; he, a young lawyer–and on a Wednesday, because they needed their friend Irving to serve as a witness and that was his day off from his optometry practice. Their marriage lasted over fifty years and was unique in their early decision not to have children and in their pursuits of art and scholarly interests.

They were well-read and practiced what they loved daily, especially when they were able to move from Chicago to Napa, California, where my own family was, and buy an almost-acre of land with an old mint-green house on it, beds for all their vegetables, a big barn where Marven made his homemade wine and ginger beer, a room for Freda to do her painting and ceramics. Well into college, I went to art classes at the senior center with Freda and her friends, who were welcoming to me though I was decades younger. We took classes in oil painting, watercolor, acrylic, and monotype.

Joking that they wanted livestock without the upkeep, they enlisted me to help them paint sheep on the side of their barn and make wooden cutout cows that we could move around the property as we pleased, just for amusement. Freda taught my younger brother to play chess. They loved to watch BBC News, and one of Freda’s favorite movies was, improbably, “Office Space.” She caught it once in syndication and then watched it every time it came on, for years after. She thought it was hilarious.

Freda purchased all of her clothing from thrift stores and her “dress shirt” was this denim Dallas Cowboys shirt, above. No one in our family cared at all for the Cowboys, who in fact may be the mortal enemies of my dad’s team, the 49ers, but she liked the fit of the shirt and wore it often. The Cowboys insignia is understated, at least.

Freda and Marven lived near a nursing home, and on more than one occasion an elderly resident would manage to wander off that property and over to theirs. The resident was always invited in, served coffee or tea, and allowed to indulge in a little freedom before either my great-aunt or uncle had the heart to call the nursing center staff and report that the missing person had been found.

Later in life, Freda took Spanish classes at the community college, and as many of her newer neighbors spoke Spanish, she went on daily walks and practiced what she was learning on them. They were incredibly patient and must have found her rather eccentric, but I took several of these walks with her and found that she seemed to connect with her neighbors genuinely, waving to them as they waved her over in turn and even invited us into several houses and garages where people were hanging out or working. To that end, her walks took a very long time. I think it once took us nearly two hours to walk a mile loop, stopping to allow her to speak stilted Spanish to many people. We went into a woman’s house so she could show us a new rocking chair she had purchased, and she gave us hibiscus tea. I was a teenager and thought Aunt Freda might embarrass me, but in the end, I was the slightly-embarrassed one, because I might not have thought to stop and talk to every single person along the route, but she did, and they seemed genuinely to enjoy her company, and no one was in any hurry to get back to anything. Later, I heard James Taylor sing that the secret of life was enjoying the passing of time, and I realized that was what she and Uncle Marven had been doing all along.

—

You might wonder what all this has to do with my conflicted feelings, this week, watching President Trump interact with the Obamas. I was kind of wondering, too. To be honest, I watched the brief footage probably five times, which seemed a little much. It was giving me a sort of heartachy revulsion that I didn’t know what to do with. And I think, to be honest, watching Michelle in particular have to shake DT’s hand made me think of her mother, and my great-aunt and uncle, and the way they interacted with the world, a way that seems old-fashioned now but in the best sense of that phrase: the way they believed that each person who appears before you should be acknowledged on their own terms, that they are unique and have a past and a story, and that something can be gained by taking the time to listen to them. That this country and this world are made up of individuals so varied and unique that all the books in the world couldn’t share everything they have to say. That our world itself is a precious and isolate thing–a “Chance Planet,” to quote the name of the ska band formed by my nature-loving, trombone-and-bass-playing Uncle Steve who left this world too soon at age 44–and that we only have one shot to save it, and it is more worth it than we can ever know or imagine.

I felt a slight personal affront, maybe, watching Michelle shake Trump’s hand. That’s not earned: I have no more reason to hate the guy than anybody; far less than some people; I am part of the “white female” demographic that helped the man into power, though I did not vote for him myself.

But a tiny bit of family pride reared its head. Hey, I wanted to say, those are our people. They should not have to stoop to shaking hands with you. The daughter of Marian Robinson should not have to shake hands with you!

My Uncle Marven and Aunt Freda have passed on now, but my brother still lives in their home. It’s a bit tattered, the well-water tainted (they have to drink bottled, for now), and the lot has been encroached upon by new housing developments capitalizing on northern California’s extreme desirability. My family could probably make a small fortune off selling that plot, but instead my brother and his roommate live there, growing their own vegetables and hops, making beer, tending the land, composting, building fences when needed, and so on. They still have much of Freda and Marven’s art on the walls, they use their homemade pottery and dishware. Maybe we are sentimental. But we like things that last.

—

About four years ago, on the cusp of yet another military move, I was hit by a wave of nostalgia and decided to look up some of our past homes–seven in thirteen years– on Google Earth. I looked back at some of the places we’d lived in Norfolk and Virginia Beach, in southern Illinois, and so on.

I noticed some changes. Shrubs removed at the Illinois home we’d doted on. I was tickled by the image from our Norfolk, Virginia condo, the second place we lived after Dave joined the navy, where, in the Google picture, my old car was still parked in the parking lot. It was like a lapse in time, a wrinkle in the Matrix–as if we were somehow still there even though the house in Illinois, where we lived later, had been updated, and was living in a future where we’d already stayed three years, had a baby, and moved on.

But here was the real kick. On a whim, I looked up Aunt Freda and Uncle Marven’s old house, where my brother now lives. There it was, in all its mint-green, ranchy splendor. The flower beds. The big old garage Uncle Marven used as his “winery,” which I can almost smell even now– its scent of wood and old wine bottles and iron and slowly rusting metals.

I zoomed in to Street View behind the house. And that’s when I saw her.

There, captured for all time, was my Aunt Freda. She had come out to the back of the house in her denim Cowboys shirt and baggy jeans and she was waving, delightedly, to the Google car, one hand raised as she strode forward. Her face was blurred, by Google policy, which was unfortunate– but clear as day, there in the center of the picture, there she was. I could almost hear her laughing. Thinking, “Holy shit, it’s the Google car! On my street! Hi, Google car!”

It was so up her alley. So very much a thing that would make her laugh.

I sat a moment, stunned. I hadn’t been expecting this. It seemed like a gift.

Thankfully, I took a screenshot. It’s saved on an older hard drive of a computer that melted down a while ago. I am planning to pay money to get all my pictures back– including the picture of Aunt Freda. I will be happy to see her again, getting a big kick out of the Google car.

—

I went onto Google Earth again tonight to see if, just by chance, that old picture might still be up, but the images had changed. Everything had been updated. The house is still there, looking more pixellated and high-tech than before. I thought of my brother and Eddie, living there now, cooking dinner for their girlfriends, feeding the stray cats, and drying herbs from the garden on top of the washer and dryer. Succulents and cacti curling on the window ledges. The screen on the mint-green back door, torn.

But in my mind’s eye, Uncle Marven is still rototilling the garden beds and Aunt Freda, delighted by the sight of the first-ever Google car she’s seen on her quiet street, is hurrying outside to wave, warmly, inviting everybody in.

Freda and Marven’s story is exactly what I needed to read this Saturday morning. I love this so much! And, I very much hope you can retrieve those pictures.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Lisa! I was thinking that I could just let things anger and disgust me, or I could focus on stuff I love, and that felt much better. xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an evocative story. You make me feel related to Uncle Marven and Aunt Freda. You put me back on New York’s Lower East Side stopping at Ratner’s Bakery or eating lox and bagels. I feel warm and comfortable, wrapped in family and tradition.

LikeLike

Thank you!! You would have liked them.

LikeLike

Wow, what a tribute to a wonderful couple. They had a synergy that elevated them and those around them. Our home, too, has some Tillin treasures: the above mentioned teapot, Marven’s tools made out of branches, and a Freda watercolor of a gull. Beautiful writing, Andria!

LikeLiked by 1 person

THANKS, DAD

LikeLike

A beautiful tribute. I liked the parts about your Uncle Marven, but really connected with the passages about Aunt Freda. They reminded me of accompanying my mother on her walking-club and Meals-on-Wheels missions. It was so interesting to see how people whom I didn’t know responded to her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Peter, thank you! It sounds like your mom was a pretty wonderful person, too.

LikeLike

This was a wonderful thing to read, Andria. I felt as if you were leading my around, introducing me to special people and without making a big deal of it, showing me what made them special. To memories. To people. To all the connections that give us a place in this world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Betsy!!

LikeLike

Andria,

I had the pleasure of spending time with Marvin and Freda at The Chapel Hill annual 4th of July gathering. Such interesting, entertaining and engaging people. I loved reading your account of their journey and remembering their joy of life. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading, Carole. I am so glad you have fond memories of them!

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this read! Thank you for sharing. I miss the Obama family as well! I’m also a big snail mail lover, so seeing those letters (older generations always seem to have better penmanship don’t they?) was so sweet! & good luck on retrieving the photos from your old computer! I need to do the same for a crashed external hard drive of mine. Also, I remember how excited my husband & I got when we spotted the google car years ago! Haha.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your comment! I’m glad you enjoyed.

P.S. I’ve never seen the Google car!!!

LikeLike

My mother, Louise Russo, also from Lawrence, Massachusetts, always spoke so fondly of Freda and Marven. Mom was so proud to show me Freda’s book, The Light at the end of the Funnel, many years ago when she received her copy from her. My Mom and Dad, Louise and John Russo, recently passed away in 2018, and I sit here reading Freda’s book after many years. They exchanged letters and Christmas cards through the years, many of which I still have in her desk. Whenever a family member was going to California, Mom would always say “you must visit my friends in Napa Valley”. Freda would enclose a list of all their crops and wine production in her Christmas card to my parents each year. Mom would proudly show it to me.

I enjoyed reading your tribute to your great-aunt and uncle very much. I would love to hear from you. Email address below. Thank you again. Linda

LikeLike