I first encountered Lauren Halloran’s writing in a Glamour essay called “Home from War, But Not at Peace.”

http://www.glamour.com/inspired/2013/home-from-war-but-not-at-peace

Lauren had won the ninth annual essay contest, which is quite an accomplishment in itself, but the content of the essay got my attention even more: she described her time as an Air Force lieutenant in Afghanistan and the trouble she had reintegrating after she returned home. I thought her writing voice was honest and engaging, and I was very much pulled into reading her piece.

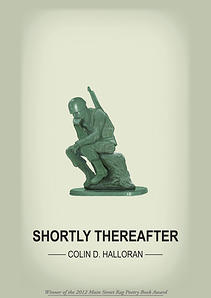

It turns out that Lauren is part of a little veteran’s writing dynasty (but, you know, a very democratic one!) with her husband, Colin Halloran, himself a veteran and a poet (I read his first collection, Shortly Thereafter, in one night, and enjoyed it very much).

Colin Halloran in Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan, 2006

Colin Halloran in Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan, 2006

They are both now quite involved with the veteran’s writing community — Colin leads writing workshops for veterans — and are actively writing, themselves; Lauren is working on a memoir and Colin has another book of poetry in the works. They were kind enough to answer some questions for me here about their military experiences, their writing, and the way they have managed to combine the two. I can’t thank them enough for being here and for their generosity with both their time and thoughts.

1. Mil Spouse Book Review: Lauren, you come from what you good-naturedly describe as “a very military family.” Your mother is a retired Army colonel who served as a nurse in the Gulf War. She also deployed when you were seven years old. I know that deployment is a stressor for so many women in the military, so I wanted to ask if you remembered much of the deployment and how you felt about it. When you first considered entering the Air Force, did your mother encourage you, or caution you against it?

LAUREN: I remember snippets from her deployment—watching the military transport bus drive away, staying with school moms while my dad was at work, and eating new things they cooked. For some reason cheese quesadillas stick in my mind. We were the only local family who had a parent deployed, so it was a very different dynamic than I experienced in the era of my military service. It was isolating because no one else was going through the same thing, but we also had tremendous support from our community. Our neighbors all pitched in cooking meals and shuttling us around to afterschool activities. Everyone put up yellow ribbons in honor of my mom, and there was a huge ribbon tied around a tree at my sister and my elementary school. I cried a lot, usually at night because Mom wasn’t there to tuck us in. We listened to tape recordings of her reading bedtime stories. We had no idea when she would come home, so that unknown element weighed on everyone. I didn’t know it at the time, but her orders were for up to two years.

I remember my dad pointing out Saudi Arabia on our office globe and watching news clips of the war effort. I had never watched the news before. One of my most vivid memories is the French braid my mom put in my hair before she left. I told her I would keep it in until she got back, and I refused to wash my hair for a long time. Eventually my dad persuaded me to wash it and let a neighbor redo the braid. Of course I remember Mom coming home. There was a huge gathering at McChord Air Force base outside Seattle, with families, supporters and media. My Girl Scout troop was even there! We had homemade signs and American flags, and I remember cheering frantically when we saw the plane approaching. We were supposed to stay behind a cordon, but when the troops started disembarking everyone swarmed onto the flightline. Lots of hugging and crying.

I think a lot about my initial decision to join the military, because it seems such an unexpected course of action after my mom deployed. I accepted my Air Force ROTC scholarship right after 9/11, but 9/11 wasn’t the reason, or at least not the conscious reason. It was more an issue of being able to afford my dream school. My parents were both supportive, but probably more wary than I acknowledged at the time. My mom didn’t pressure me either way; she just wanted to make sure I thought about the longer-term implications of a military contract. I don’t think, as an eighteen-year-old, I was really focused on the could-be’s of a few years down the road. None of us could have anticipated how embroiled the military would become in two drawn-out conflicts. It all seemed very distant and vague at that point, in the very beginning of OEF and before the invasion of Iraq, from a pristine college campus in Los Angeles.

2. I’m intrigued by how both of you – bookish, scholarly types, both admittedly sort of odd ducks within your units – came to enter the military in the first place. Lauren, we’ve already talked about your family history with the military; Colin, did you have anything similar? (I know you mention a great-uncle in one of your poems who served in WWII.)

Colin and Lauren (left and center) discussing military writing at the 2012 Boston Book Fair (with fellow veteran-writer Dario Di Battista)

Colin and Lauren (left and center) discussing military writing at the 2012 Boston Book Fair (with fellow veteran-writer Dario Di Battista)

In an interview with “Radio Boston,” Colin, you described “the strange, surprising call to duty” that spurred you to join the Army (and choose infantry as your MOS!). You’ve said that this decision even surprised yourself, having been a person who “wore Birkenstocks year-round, [had] hair down past my shoulders, carried an acoustic guitar everywhere, went to war protests.” (I could relate, somewhat – my own husband [then-boyfriend] was a UC-Berkeley history major who bewildered all our friends and family by joining the Navy in ’04. I’d been recycling his Navy recruitment pamphlets for a year whenever I’d get to the mail first.)

Looking back on it, does it make sense to you why those then-twenty-something kids that you were joined the military?

LAUREN: For me it makes sense, even though it’s not entirely clear how all those pieces came together at the time. Besides the education benefits, I was raised in a very patriotic family, and I know that service mindset was there—probably more of a sub-conscious motivator. I also didn’t have a lot of direction in terms of career goals when I graduated high school. I’d always loved writing and knew it would be a part of my life in some way, but that was about it. I signed on as an English major, and my ROTC advisors helped me find a career track (public affairs) that would allow me to utilize that skillset. I loved ROTC. It was where I felt most comfortable, around like-minded people who were passionate and hard-working. Plus, guys in uniform. 🙂 It also really gave me the structure and direction I needed at that point in my life.

COLIN: She’s just kidding about the guys in uniform thing. I think we all know she prefers purple bowties to head-to-toe camo.

LAUREN: My tastes have changed a bit.

COLIN: Anyway, I really didn’t have a strong military history on either side of my family. My grandfather served in the Navy during WWII, but was mostly stateside; I have the great-uncle I wrote about in “4th of July” who was a submariner in WWII; and I had an uncle who was drafted for Vietnam, but the war ended just a couple weeks before he was supposed to ship out.

So does it make sense? I think it does, maybe not for who I had been prior to enlisting, but for who I knew I wanted to be, and who I’ve since become (very different from who I “knew” I wanted to be back then). I wasn’t even a twenty-something yet, having just turned 19 when I signed the paperwork, and just turned 20 when I headed over to Afghanistan. I had direction, but not much of a means of getting anywhere. I was notoriously disorganized, undisciplined, and anti-authoritarian (ok, maybe that’s a little harsh, but I didn’t like taking directions from anyone but myself). I wanted to go to college, but couldn’t afford it; I wanted a career in politics, and in one of the bluest of blue states figured military service would bring in votes from the other side of the aisle; my friends and their families were stressed about a potential draft reinstatement, and I wasn’t doing much and didn’t mind going, especially if it kept someone who’d already been from going back or someone who didn’t want to go from having to; and yes, that strange and surprising “call to duty” if that’s what you want to call it. In the end, it was a way for me to challenge myself (hence going infantry—I figured I had the rest of my life to sit behind a desk), figure out a little more about who I was, serve my country, and advance closer to life goals I’d already established.

3. Both of you write very frankly, with skill and without self-pity, about your tours in Afghanistan. Lauren, you volunteered for a tour documenting rebuilding efforts in rural Afghanistan; Colin, you were part of an infantry unit on a small FOB. Both of you mention the isolation of your posts in your writing, and the grinding, ever-present awareness of potential harm. What were the hardest parts of your deployments, and how did you deal with them? Did you write during your deployments, or mainly after?

LAUREN: The hardest part for me was the disillusionment. I left for Afghanistan very idealistic—which is partly due to naivety and partly because my experiences in the military and the way the particular deployment was publicized established a certain set of expectations that ultimately came into conflict with reality. I volunteered for a Provincial Reconstruction Team because I wanted to be hands-on, not sitting behind a desk at a big base writing press releases.

Lauren with (incredibly adorable) Afghan children, Gardez City, Paktia Province, Afghanistan, 2009

Lauren with (incredibly adorable) Afghan children, Gardez City, Paktia Province, Afghanistan, 2009

But I got very frustrated by the restrictions of operating at that boots-on-the-ground level. So much of what we wanted to do got tied up in bureaucratic red tape. There was tremendous disconnect between what we were seeing and what the higher-ups directed us to do. Afghanistan is an extremely complicated place, and instead of acknowledging those complications and their underlying reasons, we could really only dabble at surface level.

I also got uncomfortable in my role as the information filter. I was communicating with both the Afghan people and the American and international publics, and what I was authorized to communicate was rarely the whole story. There was a level of censorship and “spinning,” and it often went against my personal ethical standards. A lot of deployed soldiers had valid questions and concerns about our mission—I quickly started to feel that way, too—and I started to wonder if in some indirect way I was perpetuating that cycle. Was I “selling” a corrupt government to the Afghan people? Was I selling war and American lives and treasury?

I’ve always been an emotional and pretty open-book person, but a couple months into my deployment I felt like I couldn’t be that way anymore. I had started a blog, but I got tired of self-censoring (in addition to regulations governing military blogs, I didn’t want to worry my family). In hindsight, I’m sure journaling would have been beneficial in giving me an outlet for my frustrations, but my response was to stop writing in a non-official capacity. I couldn’t find the emotional energy to do it anymore. That shutting down stayed with me when I got home. It took quite a few months and working with a therapist to help me begin to open up again. Writing proved to be a good way of sorting things out; putting my thoughts and feelings down on paper made them tangible and less overwhelming.

COLIN: To continue with the frankness, the best and really only way to deal with what I was living through on a daily basis was to accept and embrace my mortality. I knew that I was damn good at my job, but I also knew that there were things that were going to be way out of my hands no matter how prepared I was. We got hit pretty hard within our first couple of weeks in-country and one of the guys I was closest to was seriously injured. A child was killed in the same attack. I put some of that blame on myself as the convoy leader and that helped me focus and remain vigilant no matter how run down I got physically, mentally, and emotionally. A few weeks later an IED (Improvised Explosive Device) malfunctioned. I was the target. That shook me pretty hard, but I had to keep reminding myself that I was not the target, but what I represented.

Coping came through music, playing in the rare downtime I got, and listening, either in my bed/cot or on missions through the incredibly ghetto sound system I rigged up in my Humvee. The music helped me focus, unwind, and maintain some sense of normalcy amidst all the chaos.

And I didn’t write while I was there. I don’t think I could have. While I was there I needed to focus on being there, and only form of reflection I could afford was in the form of after action reports and debriefs. I think I needed some distance before I could really face it, which is why I didn’t start writing about it until I’d been home and discharged for almost two years. And I think that’s why once I started, I wasn’t able to stop.

4. Both of you describe a certain sense of disappointment, and fuzziness of mission, that you felt to some extent after your wartime service. Lauren, you write, “I volunteered thinking I’d be part of an effort that made a noticeable difference. We did celebrate some small victories. But what I noticed most was corruption winding through every layer of Afghan society, crisscrossed by a growing barricade of U.S. red tape. If we couldn’t make progress, the danger and paranoia were for nothing. How silly I’d been to think we could change the world one schoolhouse, one medical clinic, at a time.”

Colin, in the aforementioned “Radio Boston” interview, you said, “I want to feel like what I did there had a purpose — but I couldn’t tell you what that purpose is.”

How do you feel now about what you did during your deployments? Do you ever feel competing loyalties to the military and to the writer’s imperative to honesty?

LAUREN: While in the midst of it, it was easy to get discouraged by the stress and frustrations. It felt like every little progress was countered by a digression: A village would hold a pro-government meeting, then the village leader would be brutally murdered. We would fund and oversee the construction of a much-needed medical clinic or school, but the building would fall apart because contractors cut corners to pay bribes, or would be abandoned because of threats or poor maintenance.

The 2009 Presidential Election was initially a success from our vantage point because there wasn’t widespread violence, but it was ultimately marred by corruption and low voter turnout.

Though all those negative memories are still there, the more distance I get from the experience, the more I’m able to look through the fuzziness and see the positives, too. The result is a more balanced, nuanced account. One of the most difficult things about writing about a challenging or traumatic experience is to not let bitterness color the writing. I think it’s important to honestly discuss what happened without telling readers how to think or feel about it—especially with a topic like war that has tremendous socio-political implications. I struggle to find that balance every day, and I’m sure my public affairs background makes it tougher. I was basically trained to communicate in a way that encourages a specific reaction. I’m sure people in the military community take issue with some of what I write. Actually, based on the feedback I got from the Glamour essay, I know they do. But I’m okay with that. As long as I’m honest with myself in my writing. War is such a spectrum of experiences; no two perspectives will ever be exactly the same. The more people who share their story, the greater understanding the public will have, and the greater the chance that a soldier will find something to relate to.

COLIN: For the most part, I still feel pretty good about what I did, personally and with my squad, while I was over there. There were a few missions I questioned and disagreed with while I was over there, and those are the ones I remain skeptical about today, but for the most part I know that I and we did our best to help the people we were able to. There were casualties, but I understand that that is a consequence of war, no matter how unnecessary and unfortunate it may be or seem.

Much like when I was on the ground, I try to focus on the micro, not the macro. I can only control what I can control; worrying about anything else is counterproductive. And that’s how I feel about the experience now. I feel good about what I was involved with, but when I step back and look at the still ongoing war in Afghanistan as a whole, it’s difficult for me to reconcile the casualties on all sides with the very little that seems to actually have been accomplished as a whole for the country.

I say what I said to ‘Radio Boston’ because I strongly want for there to be a valid reason for the injury to my friend, the death of that young boy, all of the death, all of the destruction, the pain I feel and that I’ve put others through. But for the life of me, I still couldn’t tell you what that reason is.

5. Lauren, do you feel there are ways that your military experience differed from Colin’s because you are a woman?

LAUREN: Yes, it’s much harder to pee as a female wearing body armor. Seriously. Also of course there’s the issue of being a vast minority. I was one of seven females on my PRT of 80 people, which is actually a pretty high percentage. The ratio on our FOB was more drastic. It was a blackout FOB, and I was always on edge walking alone at night. My team was amazing and the guys were very protective, and I think because of that, and maybe because I was an officer, I never personally dealt with serious harassment. But I know women who have. It’s a terrible added stress you shouldn’t have to worry about in a war zone.

Being a woman in a bureaucratic role was interesting, because my reception from Afghan men was highly variable. Some men warily shook my hand, some skipped right over me to the male soldier on either side, some were overly enthusiastic, like I was an exciting anomaly. When females were out on missions, the Afghan media would film and take photos of us, even if we had nothing to do with what was going on. More than once I ended up on the government news station. It was weird and uncomfortable and sometimes deflected the focus from the mission.

The best part about being a deployed female was that I could talk to Afghan women. We sat in on women’s affairs meetings and PRT-sponsored training programs for women, like midwifery training or civics training educating women about their constitutional rights. I found all the women unbelievably beautiful and inspiring. They spoke candidly about wanting to build a better future for their children and were so grateful for us leaving our families to come work with them. And I loved the little girls. They tended to be pushed around by the boys, and we all hoped that seeing females in uniform, doing the same things as the men, would be empowering to them. Colin and I have talked about adopting an Afghan girl someday.

COLIN: This is why it’s so important for Lauren and others to share their accounts. There wasn’t a single female on either of the FOBs where I was stationed. No deployment experience is the same; that’s why it’s so important we get as many narratives out as possible.

6. To open your poem “Spring Offensive,” Colin, you quote Mahmoud Darwish:

Sadness is a white bird that does not come near a battlefield.

Soldiers commit a sin when they feel sad.

Both of you have struggled with the reintegration process since your return home. Colin, you lead workshops for veterans and civilians to help them understand war through writing. Lauren, your essay in Glamour described the shame and fear you felt in seeking help for your own Chronic Adjustment Disorder, which you describe as “PTSD lite,” but ended on the more hopeful note of gradual recovery and having met Colin. How has this connection with other veterans developed over the last few years, and how important has talking with like-minded or sympathetic people been to your recovery?

LAUREN: We both get pretty fired up talking about veteran mental health because it’s such a poorly handled topic. For a long time no one talked about it. Now, PTSD is kind of a trendy issue, but it’s discussed in a very sensationalized way. The media focuses on extreme cases where a veteran has totally debilitating PTSD or where someone “snaps” and commits a violent crime. Dr. Phil had a segment literally titled “PTSD takes veterans from heroes to monsters.” Obviously those things happen, and we as a society need to do a better job of supporting people who are suffering to that degree. But there is a whole range of mental health that isn’t acknowledged. It’s not black and white, you’re totally fine or you’re a danger to yourself and everyone around you. The vast majority are somewhere in the middle: fully-functional adults contributing positively to society, but who have triggers and sometimes struggle with complicated emotions or reactions to stimuli.

The lack of discussion about that gray area was part of what was so hard for me when I redeployed. I knew I was having issues, but they weren’t in line with what I knew about PTSD. And there’s this idea that you have to earn the right to have mental health issues. I hadn’t been in direct combat, so I didn’t feel like I’d earned it. That made me feel guilty, which just amplified everything else. I know now that it’s a neuro-chemical issue. Science is finally at a point where we can see that. Everyone is programmed differently and responds differently to situations. You can’t choose whether or not you’ll suffer or to what degree.

That issue—being a non-combat veteran who struggled with readjustment—is a big part of what I write about because I think like it’s an important missing piece of the discussion. For me, the goal of veteran writing is twofold (besides personal reasons): to share your story with other veterans so they can find elements to relate to, and also to promote better understanding in the general public and hopefully build a better support system. Like I said earlier, the more narratives there are, the greater our understanding of war will be.

There’s a growing veteran writing community, and it’s amazing. Colin and I have both been so inspired reading or listening to work by other veterans. There aren’t a lot of creative outlets in the military, and it’s incredible what happens when vets find one. We all tend to relate on multiple levels, as veterans and as artists. That’s a pretty incredible instant bond. And even though our experiences are all so different, there are always similarities. My mom and I connected in a new way when I started talking to her about my deployment; she was able to open up for the first time about a lot of her own post-deployment struggles—twenty years later! That was also what initially drew me to Colin. I read a few of his poems and thought, “holy crap, this guy reached into my head and knows exactly how I feel!” The rest, as they say, is history.

COLIN: As is so often the case, Lauren has said it much better than I ever could. But I’ll try to add something.

Obviously, sharing my story with fellow vets and non-vets alike has literally changed my life. I often say, because it’s true, that writing saved my life. Without that creative outlet, I’m sure I would have succumbed to my self-destructive tendencies.

And sharing followed from the writing. It was not only a way to get the negative energy out of myself, but to put it out in the world, not to hurt the world, but as an inquiry. And I got responses. I got responses from other writers, who helped me hone my craft, make me better at transposing my inner-turmoil. I got responses from fellow-vets, who related. I got responses from other vets who write, the beginning of what has turned into great friendships and collaborations. I got responses from people in my life, who after being pushed away were able to begin to understand why I had become the person I was.

And sharing followed from the writing. It was not only a way to get the negative energy out of myself, but to put it out in the world, not to hurt the world, but as an inquiry. And I got responses. I got responses from other writers, who helped me hone my craft, make me better at transposing my inner-turmoil. I got responses from fellow-vets, who related. I got responses from other vets who write, the beginning of what has turned into great friendships and collaborations. I got responses from people in my life, who after being pushed away were able to begin to understand why I had become the person I was.

And for me, the most important response was that I entered treatment. People sometimes hear the word “therapy” and get uncomfortable. But put the word “physical” in front of it and it’s not an issue. If someone injures their leg or arm, they receive medication, they go to physical therapy and have to work hard, often painfully, to rehab the injured part back to its pre-injury state. That’s exactly what I’m doing. PTSD is not a disorder so much as an injury (there’s a movement to get the “D” removed, but that’s a discussion for another day). The brain alters its physiology, its neurochemistry, in the extreme and prolonged stress of war. And there are other effects that come with that, just as a broken bone will often lead to atrophied muscles. The approach to healing and restoration is the same, but only one comes with the stigma. And that’s what we’re working against.

I think it’s important to note a couple of things here. First, Lauren’s essay in Glamour rang true with me as well, as I, even to this day, feel guilt over my PTSD. One thing that the backlash she received after the essay’s publication revealed was something I had known for some time: we can all point to someone who had it better than us; we can all point to someone who had it worse. Second, I think it’s important that I make clear that this is a process for me. I still have PTSD. I still have days where I simply can’t leave the house. I still have nights where I lose myself, looking for answers at the bottom of a bottle, feeling unworthy of both the pain I feel and the happiness I’ve found, lost in some hazy emotional purgatory. They are certainly fewer and further between than they were six years ago, but they’re still there, lurking, waiting to come out.

I may be the one leading workshops and giving lectures, but I always walk away from them having learned something as well. Healing, it’s a process, a journey, not a destination. For me, that’s the most important thing I’ve learned, the most important thing I can share with others who find themselves in similar situations. I shared my story. I didn’t realize at first, but my writing was me reaching out to the world for help, for some semblance of an answer. And I’m still writing. And I’m still reaching out, asking questions, reflecting, writing more. I’m still in treatment. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that.

7. What are you both working on now?

LAUREN: Other than preparing to spend the rest of our lives in holy matrimony?

Wedding day, July 12, 2014, at the Seattle Public Library (photo by Victoria Porto, Victoria Porto Photography). Congratulations, guys!

Wedding day, July 12, 2014, at the Seattle Public Library (photo by Victoria Porto, Victoria Porto Photography). Congratulations, guys!

I just graduated from the Emerson College creative writing MFA program, so I’m working on turning my thesis manuscript into a full-length memoir about my mother’s and my service.

COLIN: I have another poetry manuscript that is out under consideration at a whole bunch of publishers. It’s not quite a sequel to Shortly Thereafter, but it picks up thematically where that collection left off, using metaphor, persona, and reflective narrative to further explore the challenges and struggles of my adjustment/reintegration journey. I won’t lie, it gets pretty dark, but I was in a pretty dark place while I was writing most of it. Like Shortly Thereafter, I wanted the book to have an overall narrative arc, and that structure is a mirror of my spiral into darkness. But I like to think it ends on a note of hope, reflecting where I am now.

Next up is a prose memoir that I’ve started, but will likely be working on for quite some time. Having already explored the material through poetry in order to reach its emotional core and essence, I find that prose allows me to explore it in a broader, more philosophical and academic manner.

Also, I’m incredibly honored to be judging the poetry contest for this year’s Proud to Be: Writing by Warriors (Vol. 3).

8. Finally –

Colin, I love your lines in the poem “4th of July”

I fire off some flares

and wonder what this will look like

when my mind’s had

sixty years to shape it.

Any closing thoughts? Anything else you want to say about your experiences as writers, veterans?

LAUREN: Everyone should read work by and about veterans. It’s important, but also just really stinking good. And there are many resources out there for veterans wanting to give writing—or other creative endeavors—a try. Veterans Writing Project, Warrior Writers, Combat Paper Project, Words after War . . . It’s a growing community full of wonderful, intelligent, supportive people.

COLIN: I think that the most important thing I’ve learned through all of this is that no matter how isolated and alone you feel or think you are, you’re not. But the only way to discover that is to share your story and give others the opportunity and safe space to share theirs. It can be incredibly difficult to open up and share, but in the end, it is so worth it. And who knows, you may even meet your spouse because of it.

Lauren and Colin, thank you so much for joining me here! I’m eager to keep up with whatever you write!

———————————————–

Lauren Halloran blogs at UNCamouflaged. She’s also featured in the collection There: Writings on Returnings.

Colin Halloran has a poetry collection, Shortly Thereafter, and maintains a blog here.

Both Lauren and Colin have writing in the anthology Proud to Be: Writing by American Warriors.

What interesting people! Fascinating to hear about the thriving veteran’s writing community.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, Dave! Definitely check out the military writing from the last few years. I’m thrilled that more books by and about women are hitting the shelves too.

LikeLike

I want to thank both Colin and Lauren for their service and for being so vocal about veterans’ issues! I especially loved what Lauren had to say about how sensationalized PTSD is. It’s as a soldier will only get it if they’ve seen horrible, traumatic things. And then, they soldier is “expected” to lash out, become an alcoholic, have nightmares. That type of response is important to normalize, but it isn’t the only experience.

I wouldn’t not say that my husband had PTSD after his first deployment, but we struggled mightily with reintegration. It didn’t help that it felt like no one else was talking about it. It was as if everyone else came home to happily ever after. That made it so much more difficult for me to realize what we were dealing with and to come to terms with it. Once again, thank you, thank you, thank you for talking about what you talk about and doing what you do!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your comments, Amy. I think what you and your husband experienced is very common, but for some reason it isn’t discussed within the military or in the general public. No one should ever have to have their post-deployment struggles validated. I hope you two have reached a place of understanding and that you’re doing well. Please know there are many people ready to listen and many organizations ready to help should you ever need it! I’ll also recommend Siobhan Fallon’s wonderful book “You Know When the Men are Gone,” which discusses deployments from the military wife/family perspective. Best wishes to you both.

LikeLike